The ‘Golden’ period for Lviv Jewish community was a time of the reign of King Jan III Sobieski (the 16th – the first half of the 17th centuries). Not only did he grant them many privileges but also favored some Jews such as Dr. Emanuel de Jonas, who became his personal doctor, and Betsal (Bezalel), a royal tax collector. Many Jews attained a high social status as financiers, doctors and teachers in this period; their religious and cultural spheres of life were developing quickly. The period of the Austrian Empire, which lasted from 1772 to 1918, was more difficult for the Jews since they had to fight for their rights and try hard to preserve their traditions as well as together with new movements and changes create their own cultural identity. As it was already mentioned, Lviv was a city with several religious movements that coexisted and were in conflict with each other. Therefore, it was a time of active searching and challenges caused by modernization for all city communities, including Jewish as a second largest. By the end of the 19th century Lviv Jewish community had numerous synagogues, schools, libraries, hospitals, and philanthropic organizations. In 1910, the Jews of Lviv made up about 25% of the population and were of different professions (70% of lawyers, 70% of Chamber of Commerce members, 60% of doctors). About 1,500 Jews studied in Lviv University in 1910 (33% of all students), there were several Jewish student unions and Jewish lecturers. On the other hand, even though the community was the second largest there were still prejudices and restrictions. For example, in 1870 during the elections to the city council there was an unwritten rule that a Jew cannot be a mayor of the city, maximum a vice mayor. A similar situation was for Ukrainian-Rusyns, the third largest community. On our second route you will get to know the cultural and intellectual Jewish Lviv at the end of the 19th–beginning of the 20th century which life was abruptly interrupted the Nazi occupation.

V. Chornovola Avenue divides the ghetto area into two parts. We will start at Kulisha Street, which was a business center of suburban Jewish quarter until the mid-twentieth century. Its first name was Soniachna (Sunny) and it was believed that the street was called this way because of the synagogue ‘Or Shemesh’ (‘The Light of the Sun’) which was in the courtyard of the house on 26 Kulisha Street. In 1842, the synagogue was rebuilt, and in 1903 it was relocated to Medova Street where it used to be before the Second World War. At present there is a playground on its place.

V. Chornovola Avenue divides the ghetto area into two parts. We will start at Kulisha Street, which was a business center of suburban Jewish quarter until the mid-twentieth century. Its first name was Soniachna (Sunny) and it was believed that the street was called this way because of the synagogue ‘Or Shemesh’ (‘The Light of the Sun’) which was in the courtyard of the house on 26 Kulisha Street. In 1842, the synagogue was rebuilt, and in 1903 it was relocated to Medova Street where it used to be before the Second World War. At present there is a playground on its place.

The Jewish cultural prosperity in Lviv, that was a part of Poland at that time, took place in 1920s. At 23-26 Kulisha Street there was a ‘Colosseum’ theater which could seat more than 1,000 spectators. The first mention about the theater dates back to 1911. This was not the first Jewish theater in Lviv but it was very diverse, especially in the interwar period. The troupes of the famous Warsaw theaters, local and visiting well-known directors and actors were performing here, and also there were shows on legerdemain, acrobatics and humor, various concerts, and some time a movie theater. It was a center of cultural and entertainment life in the quarter.

The Jewish cultural prosperity in Lviv, that was a part of Poland at that time, took place in 1920s. At 23-26 Kulisha Street there was a ‘Colosseum’ theater which could seat more than 1,000 spectators. The first mention about the theater dates back to 1911. This was not the first Jewish theater in Lviv but it was very diverse, especially in the interwar period. The troupes of the famous Warsaw theaters, local and visiting well-known directors and actors were performing here, and also there were shows on legerdemain, acrobatics and humor, various concerts, and some time a movie theater. It was a center of cultural and entertainment life in the quarter.

Moving towards the beginning of the Kulisha Street, we will turn right to the M. Balabana Street.

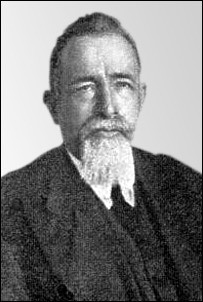

Mayer Samuel (Shmuel) Balaban (1877-1942) was a prominent historian and researcher, the author of theses on the history of Jews in Ukraine, Poland and Austria. It was him who substantiated the opinion that the oldest Jewish community in Lviv emerged in the times of King Danylo reign (13th century) in Pidzamche suburb. He based his researches on the documents about the history of Jews in Lviv in the 16th – 19th centuries. He was a founder of public ‘Zion’ organization where he taught Jewish history. M. Balaban is considered to be a founder of the historiography of Polish Jewry, especially, of their community life.

In the house No. 1 on the M. Balabana Street in 1910 lived a rabbi Neuhaus Sindel.

Moving towards the beginning of the Kulisha Street, we will turn right to the M. Balabana Street.

Mayer Samuel (Shmuel) Balaban (1877-1942) was a prominent historian and researcher, the author of theses on the history of Jews in Ukraine, Poland and Austria. It was him who substantiated the opinion that the oldest Jewish community in Lviv emerged in the times of King Danylo reign (13th century) in Pidzamche suburb. He based his researches on the documents about the history of Jews in Lviv in the 16th – 19th centuries. He was a founder of public ‘Zion’ organization where he taught Jewish history. M. Balaban is considered to be a founder of the historiography of Polish Jewry, especially, of their community life.

In the house No. 1 on the M. Balabana Street in 1910 lived a rabbi Neuhaus Sindel.

The ‘Beit Cwi Zef Rapp’ hasidic synagogue was functioning in the house No. 5 in 1906. There was also a Jewish charitable association ‘The House of Rapp’ funded by the owner of the building.

In the courtyard of the stonehouse No. 8 there was built a ‘Meleseh Enoch’ synagogue. It was rebuilt after the World War II.

In the courtyard of the stonehouse No. 8 there was built a ‘Meleseh Enoch’ synagogue. It was rebuilt after the World War II.

We come back to the Kulisha Street and move towards Shpytalna Street. On the facade of the house No. 1-3 you can see the restored prewar inscriptions of the former Jewish store in Yiddish and Polish.

On the left there used to be a synagogue for the study of Torah built in 1877. The temple was destroyed in 1941 and since then this area has remained undeveloped.

On the left there used to be a synagogue for the study of Torah built in 1877. The temple was destroyed in 1941 and since then this area has remained undeveloped.

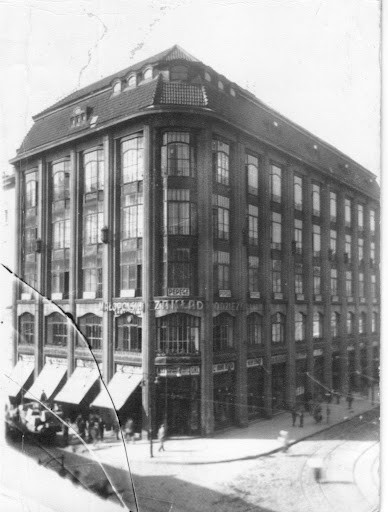

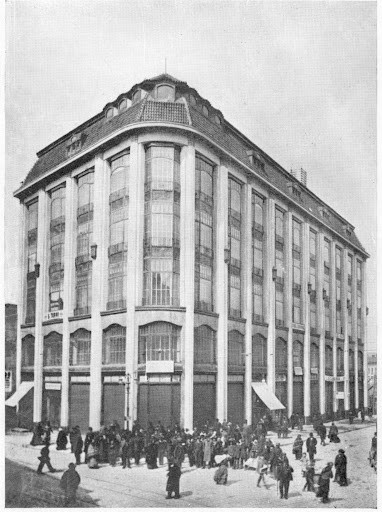

On the crossing with Shpytalna Street you can see the first Lviv supermarket, “Magnus” (Domy towarowe Magnus), built in 1912 according to the project of R. Felinski, at the request of Jewish tradesmen, who united their interest around the enterprise of the Frenkel family. The supermarket was built according to American trade centers style, popular at that time.

On the crossing with Shpytalna Street you can see the first Lviv supermarket, “Magnus” (Domy towarowe Magnus), built in 1912 according to the project of R. Felinski, at the request of Jewish tradesmen, who united their interest around the enterprise of the Frenkel family. The supermarket was built according to American trade centers style, popular at that time.

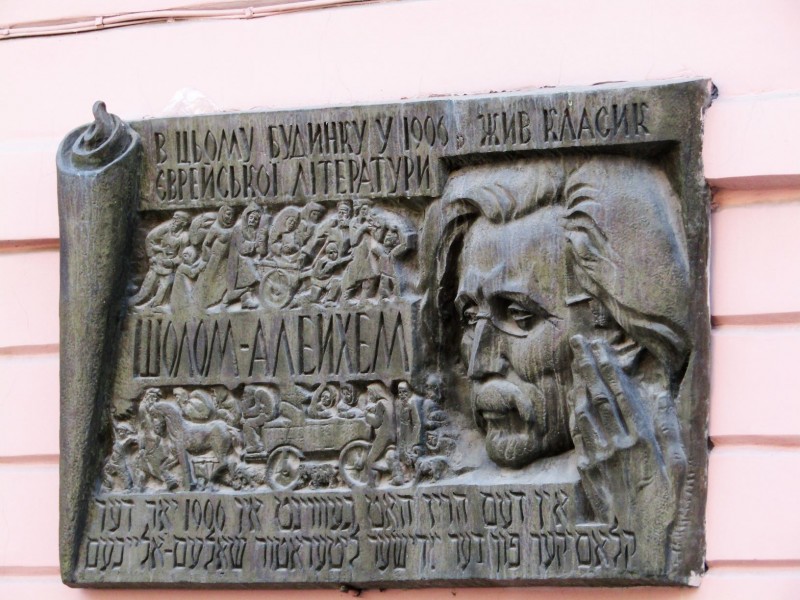

At the intersection of Shpytalna and Kotliarska Streets you can see a memorial plaque. It tells about the famous Jewish classic poet Shalom Aleichem who lived in this building in 1906.

At the intersection of Shpytalna and Kotliarska Streets you can see a memorial plaque. It tells about the famous Jewish classic poet Shalom Aleichem who lived in this building in 1906.

In the house No. 14 lived a famous painter-impressionist Erno Erb in 1878-1942. His paintings are exhibited in the museums of Krakow and Warsaw, in Lviv Art Gallery and in the Museum of Ukrainian Art in Lviv. Erb studied at the Berlin Academy of Arts where he was significantly influenced by Max Lieberman. At the end of the 1930s he was a member of the Association of Independent Ukrainian Artists and their first exhibitor.

In the house No. 14 lived a famous painter-impressionist Erno Erb in 1878-1942. His paintings are exhibited in the museums of Krakow and Warsaw, in Lviv Art Gallery and in the Museum of Ukrainian Art in Lviv. Erb studied at the Berlin Academy of Arts where he was significantly influenced by Max Lieberman. At the end of the 1930s he was a member of the Association of Independent Ukrainian Artists and their first exhibitor.

Shpytalna and Kotliarska Streets are connected by Tamanska Street. The Jewish industrial school and State school named for Thaddeus Chatskyi (1891) were on this street. During the occupation the Judenrat Nazi mandated Jewish council and a hospital were in this school.

Shpytalna and Kotliarska Streets are connected by Tamanska Street. The Jewish industrial school and State school named for Thaddeus Chatskyi (1891) were on this street. During the occupation the Judenrat Nazi mandated Jewish council and a hospital were in this school.

The neighboring street is named for Simon Leimberg, the head of the Jewish department in the Ukrainian Galician army.

An eminent Jewish politician, lawyer and journalist Gershom Tsipper (1868-1920) lived on this street in the house No.10

An eminent Jewish politician, lawyer and journalist Gershom Tsipper (1868-1920) lived on this street in the house No.10

Near the Rappoporta Street there is street for Sholom Aleichem, the famous Jewish writer (lived on Kotliarska Street in Lviv, in 1906). The cultural and educational association of Jewish artisans ‘Jad Charuzim’ was functioning in house No. 11 in 1916. There was a stage and a hall where various cultural events, particularly performances, were held.

Near the Rappoporta Street there is street for Sholom Aleichem, the famous Jewish writer (lived on Kotliarska Street in Lviv, in 1906). The cultural and educational association of Jewish artisans ‘Jad Charuzim’ was functioning in house No. 11 in 1916. There was a stage and a hall where various cultural events, particularly performances, were held.

The house No. 12 was built in 1899 specifically for the Board of the Jewish community in Lviv. There was a large hall which was named in honor of Emil Byk. Since the proclamation of Ukrainian independence the Lviv Center for Jewish Studies and Jewish Education as well as the International Center ‘Holocaust’ named after Dr. A. Schwarz and Lviv regional charitable organization Bnei Brit ‘Leopolis’ named after E. Domberg has been functioning here.

Doctor Emil Byk (1845-1906) was one of the most famous personalities in Lviv. He was a Deputy of Vienna Parliament and a head of the Lviv Jewish community, the founder of ‘Bney-Brit’ organization and a famous Galician philanthropist. The hospital on Rappoporta Street, the house of Jewish community administration and the shelter for orphans and widows (2B Rappoporta Street) were built with his support.

The house No. 12 was built in 1899 specifically for the Board of the Jewish community in Lviv. There was a large hall which was named in honor of Emil Byk. Since the proclamation of Ukrainian independence the Lviv Center for Jewish Studies and Jewish Education as well as the International Center ‘Holocaust’ named after Dr. A. Schwarz and Lviv regional charitable organization Bnei Brit ‘Leopolis’ named after E. Domberg has been functioning here.

Doctor Emil Byk (1845-1906) was one of the most famous personalities in Lviv. He was a Deputy of Vienna Parliament and a head of the Lviv Jewish community, the founder of ‘Bney-Brit’ organization and a famous Galician philanthropist. The hospital on Rappoporta Street, the house of Jewish community administration and the shelter for orphans and widows (2B Rappoporta Street) were built with his support.

Now we are walking down the Ya. Rappoporta Street. Yakiv (Jacob) Rappoport (1772-1855) was a famous doctor and social activist. He was born in Uman in a rabbis family. After completing a philosophy degree, he decided to work in the area of medicine and was quite successful. Rappoport was considered to be the best doctor in Lviv, and was one of the first doctors in the world who supported universal vaccination.

The events that took place in the Jewish community of Lviv in the middle and in the second half of the 19th century were characterized by the increasing of Jewish education role and the creation of a wider network of charitable institutions among which a leading position belonged to a Jewish hospital. ‘Bet Chulim’ Jewish hospital was built in 1898-1901 in the Moorish style. Today it is the maternity department of the city hospital. Its founder, a philanthropist Maurycy Lazarus, was an outstanding personality. He dreamed of becoming a painter but finally became a successful businessman. The mortgage bank that he created and led for forty years was one of the most popular in Galicia. To create the hospital Lazarus spent 300 thousand korons and his wife provided the best medical equipment in the city. The administration of the hospital was extremely influential in the Jewish community. All cemeteries, bath-houses, ritual slaughter houses, as well as several houses were in its control. There were a few well-known doctors working in the hospital. Almost a third of all patients of the Jewish hospital were Christians.

Now we are walking down the Ya. Rappoporta Street. Yakiv (Jacob) Rappoport (1772-1855) was a famous doctor and social activist. He was born in Uman in a rabbis family. After completing a philosophy degree, he decided to work in the area of medicine and was quite successful. Rappoport was considered to be the best doctor in Lviv, and was one of the first doctors in the world who supported universal vaccination.

The events that took place in the Jewish community of Lviv in the middle and in the second half of the 19th century were characterized by the increasing of Jewish education role and the creation of a wider network of charitable institutions among which a leading position belonged to a Jewish hospital. ‘Bet Chulim’ Jewish hospital was built in 1898-1901 in the Moorish style. Today it is the maternity department of the city hospital. Its founder, a philanthropist Maurycy Lazarus, was an outstanding personality. He dreamed of becoming a painter but finally became a successful businessman. The mortgage bank that he created and led for forty years was one of the most popular in Galicia. To create the hospital Lazarus spent 300 thousand korons and his wife provided the best medical equipment in the city. The administration of the hospital was extremely influential in the Jewish community. All cemeteries, bath-houses, ritual slaughter houses, as well as several houses were in its control. There were a few well-known doctors working in the hospital. Almost a third of all patients of the Jewish hospital were Christians.

Ya. Rappoporta, Kleparivska and Dzherelna Streets outline the area, where in 1414 the Jewish cemetery (kirkut) was founded. The Lviv cemetery was one of the oldest in Europe and became the final resting place for many Galician Jews. Such respected Jewish leaders as Levi ben Yaakov Kikines (1503), Kalman from Vorms (1560), Dr. Isaac Nachmanowicz, Yehoshua ben Eliyahu Falk – rector of Lviv yeshiva, and rabbi Abraham Kohn were buried here. In August 1855, after a city-wide cholera outbreak, the number of burials increased. It caused the closing of the cemetery and the opening of a new one at Yaniv suburb. During the war, Nazis destroyed most of the graves and in 1947 on the place of the Old cemetery the Soviet authorities set the open-air market ‘Krakivskyi’, which still operates today.

Ya. Rappoporta, Kleparivska and Dzherelna Streets outline the area, where in 1414 the Jewish cemetery (kirkut) was founded. The Lviv cemetery was one of the oldest in Europe and became the final resting place for many Galician Jews. Such respected Jewish leaders as Levi ben Yaakov Kikines (1503), Kalman from Vorms (1560), Dr. Isaac Nachmanowicz, Yehoshua ben Eliyahu Falk – rector of Lviv yeshiva, and rabbi Abraham Kohn were buried here. In August 1855, after a city-wide cholera outbreak, the number of burials increased. It caused the closing of the cemetery and the opening of a new one at Yaniv suburb. During the war, Nazis destroyed most of the graves and in 1947 on the place of the Old cemetery the Soviet authorities set the open-air market ‘Krakivskyi’, which still operates today.

To get to the New Jewish cemetery you should walk up Zolota (Golden) Street. Legend tells that the name of the street is derived from the gold that fell from hearses while they were carrying tombs to the cemetery. Near the cemetery, between the buildings No. 40 and 40-а, there was a stadium of ‘Hasmonea’, a Jewish sport club in the interwar period.

The New cemetery was opened in August, 1855. In 1856 the synagogue was built here by funds provided by Jewish tradesman Efraim Wiksel. In 1912 according to the project of Roman Feliński and Jerzy Grodyński the construction of a pre-internment chapel, Beit Tahar, was started. During the Second World War all the buildings and graves were destroyed.

To get to the New Jewish cemetery you should walk up Zolota (Golden) Street. Legend tells that the name of the street is derived from the gold that fell from hearses while they were carrying tombs to the cemetery. Near the cemetery, between the buildings No. 40 and 40-а, there was a stadium of ‘Hasmonea’, a Jewish sport club in the interwar period.

The New cemetery was opened in August, 1855. In 1856 the synagogue was built here by funds provided by Jewish tradesman Efraim Wiksel. In 1912 according to the project of Roman Feliński and Jerzy Grodyński the construction of a pre-internment chapel, Beit Tahar, was started. During the Second World War all the buildings and graves were destroyed.

Some of the gravestones were transported to Germany. Today the remainder of the Jewish cemetery is preserved only on the side of Yeroshenka Street. After the war, an obelisk was placed for the mass grave of the Nazis victims executed between 1942-1943, but without a single word that the victims were Jews. The concealment of this fact and the fact that the victims were actually killed because they were Jews is a feature of the Soviets Holocaust denial. Lviv lawyer Dr. Emmanuel Blumanfeld, Dr. Emil Byk, famous Jews: Shlomo Buber, rabbi Yekhezkel Karo, Nathan Lauvenshtain, the deputy of parliament, and others were buried here. Almost the three-fourth of the New Jewish cemetery area is occupied by Christians buried in Jewish graves. In the southern part of the cemetery there are about hundred of Muslim graves. Jewish entombments (after 1944) are located on several fields near the main walkway.

Some of the gravestones were transported to Germany. Today the remainder of the Jewish cemetery is preserved only on the side of Yeroshenka Street. After the war, an obelisk was placed for the mass grave of the Nazis victims executed between 1942-1943, but without a single word that the victims were Jews. The concealment of this fact and the fact that the victims were actually killed because they were Jews is a feature of the Soviets Holocaust denial. Lviv lawyer Dr. Emmanuel Blumanfeld, Dr. Emil Byk, famous Jews: Shlomo Buber, rabbi Yekhezkel Karo, Nathan Lauvenshtain, the deputy of parliament, and others were buried here. Almost the three-fourth of the New Jewish cemetery area is occupied by Christians buried in Jewish graves. In the southern part of the cemetery there are about hundred of Muslim graves. Jewish entombments (after 1944) are located on several fields near the main walkway.